The Blue Lotus is Victory of Spirit over the senses. It signifies Wisdom of Knowledge. In various parts of the world, it has been a symbol of fertility, sunlight, transcendence, beauty and above all "Purity". The Lotus is one of the most ancient and deepest symbols of the planet. The sun-god who formed himself from chaos of Nun emerged from the Lotus petals as Ra. The forth Dynasty Egyptians greatly valued the "Sacred Lotus".

KEMETIC SCIENCE

Positive Progress Through The Benevolent Use Of Knowledge

Thursday, February 12, 2009

Queen of Fire

*Dream Stella*

Wednesday, February 11, 2009

The Ahmes Papyrus

The Ahmes was written in hieratic, and probably originated from the Middle Kingdom: 2000-1800 BC. It claims to be a ``thorough study of all things, insight into all that exists, knowledge of all obscure secrets." In fact, it is somewhat less. It is a collection of exercises, substantially rhetorical in form, designed primarily for students of mathematics. Included are exercises in

fractions

notation

arithmetic

algebra

geometry

mensuration The practical mathematical tools for construction?

To illustrate the level and scope of Egyptian mathematics of this period, we select several of the problems and their solutions as found in the two papryi. For example, beer and bread problems are common in the Ahmes.

Problem 72. How many loaves of "strength" 45 are equivalent to 100 loaves of strength 10? Fact:

strength := Invoking the rule of three 5 , which was well known in the ancient world, we must solve the problem:

Answer : loaves.

Problem 63. 700 loaves are to be divided among recipients where the amounts they are to receive are in the continued proportion

Solution. Add

The first value is 400. This is the base number. Now multiply each fraction by 400 to obtain the recipient's amount. Note the algorithm nature of this solution. It reveals no principles at all. Only when converting to modern notation and using modern symbols do we see that this is correct We have

etc. This will be the case if there is a base number such that

Thus

Now add the fractions to get and solve to get

Now compute .

The solution of linear algebra problems is present in the Ahmes. Equations of the modern form

where and are known are solved. The unknown, , is called the heep . Note the rhetorical problem statement.

Problem 24. Find the heep if the heap and a seventh of the heep is 19. (Solve .)

Method. Use the method of false position . Let be the guess. Substitute . Now solve . Answer: . Why?

Solution. Guess .

Answer:

Geometry and Mensuration Most geometry is related to mensuration. The Ahmes contains problems for the areas of

isosceles triangles (correct)

isosceles trapezoids (correct)

quadrilaterals (incorrect)

frustum (correct)

circle (incorrect)

curvilinear areas

In one problem the area for the quadrilateral was given by

which of course is wrong in general but correct for rectangles. Yet the ``Rope stretchers" of ancient Egypt, that is the land surveyers, often had to deal with irregular quadrilaterals when measuring areas of land. This formula is quite accurate if the quadrilateral in question is nearly a rectangle.

The area for the triangle was given by replacement in the quadrilateral formula

On Rigor

There is in Egyptian mathematics a search for relationships, but the Egyptians had only a vague distinction between the exact and the approximate . Formulas were not evident. Only solutions to specific problems were given, from which the student was left to generalize to other circumstances. Yet, as we shall see, several of the great Greek mathematicians, Pythagoras , Thales, and Eudoxus to name just three, went to Egypt to study. There must have been more there than some student exercises to consider!

Problem 79. This problem cites only ``seven houses, 49 cats, 343 mice, 2401 ears of spelt, 16,807 hekats."

Note the similarity to our familiar nursery rhyme:

As I was going to St. Ives,

I met a man with seven wives;

Every wife had seven sacks,

Every sack had seven cats,

Every cat had seven kits.

Kits, cats, sacks, and wives,

How many were going to St. Ives? This rhyme asked for the very impractical sum of all and thus illustrates some knowledge and application of geometric progressions.

Problem 50. A circular field of diameter 9 has the same area as a square of side 8. This gives an effective .

Problem 48 gives a hint of how this formula is constructed.

Trisect each side. Remove the corner triangles. The resulting octagonal figure approximates the circle. The area of the octagonal figure is:

Thus the number

plays the role of . That this octagonal figure, whose area is easily calculated, so accurately approximates the area of the circle is just plain good luck. Obtaining a better approximation to the area using finer divisions of a square and a similar argument is not easy.

Geometry and Mensuration Problem 56 indicates an understanding of the idea of geometric similarity. This problem discusses the ratio

The problem essentially asks to compute the for some angle . Such a formula would be need for building pyramids.

Note the obvious application to the construction of a pyramid for which the formula for the volume, , was known. (How did they find that?)

Geometry and Mensuration The are numerous myths about the presumed geometric relationship among the dimensions of the Great Pyramid. Here's one:

[perimeter of base]=

[circumference of a circle of radius=height] Such a formula would yield an effective , not , as already discussed.

Next: The Moscow Papyrus Up: $FILE Previous: Counting and Aritmetic

Don Allen 2001-04-21

Thursday, February 5, 2009

The Hell of Ancient Egypt*

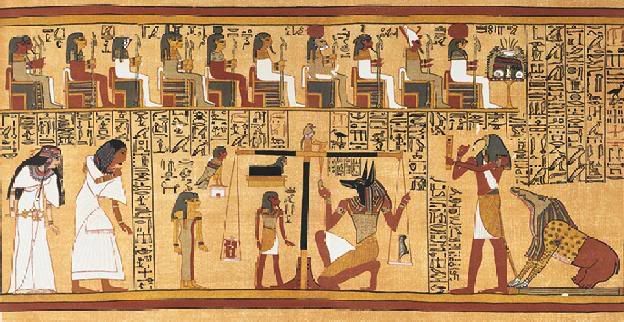

"Papyrus of Ani"---Weighing of the Heart"*

God, during civilization's early years, was not much of a public figure. Indeed, prior to Moses, even the Jew's appear to have worshipped pagan gods, and apparently, prior to the handing down of the Ten Commandments, he was "unpublished". In fact, most scholars believe that, only much later, were the earliest books of the Bible provided to mankind. Early on, God seems to have revealed himself to specific individuals, but not necessarily to his creations in general.

Therefore, the Christian, Jewish and Islamic visions of the afterlife are relatively new ones, including their concept of hell. In fact, hell may very well have been invented by the ancient Egyptians, at least as a public reference. To put the whole of this more simply, the recorded concept of hell in ancient Egypt predates the recorded concept of hell in our modern religions.

The principal sources for our knowledge of the Egyptian concept of hell are the Books of the Netherworld which are found inscribed on the walls of the royal tombs of the New Kingdom in the Valley of the Kings at Thebes, and then later on papyrus and other funerary objects belonging to commoners.

The concept of hell in the ancient Egyptian religion is very similar to those of our modern religions. Those who were judged unfavorably faced a very similar fate to our modern concept of hell, and perhaps even more specifically to the more Middle Age concept of it as a specific region beneath the earth. For the damned, the entire, uncontrollable rage of the deity was directed against those who were condemned through their evils. They were tortured in every imaginable way and "destroyed", thus being consigned to nonexistence. They were deprived of their sense organs, were required to walk on their heads and eat their own excrement. They were burned in ovens and cauldrons and were forced to swim in their own blood, which Shezmu, the god of the wine press, squeezed out of them.

One difference between our modern concept of heaven and the ancient Egyptian one is that even the blessed faced perilous obstacles in the Netherworld, such as demons that guarded the gates of the netherworld, which required a knowledge of spells to overcome. It sometimes appear that they had to travel through the same hell of the damned, but conceptually, at least, they occupied a very different space.

This nocturnal journey of the blessed, along with the sun god through the underworld was not a prominent theme in the oldest royal mortuary literature, the Pyramid Text and the descriptions of hell are therefore absent from these spells. By contrast, the concept that emerges from the Books of the Netherworld is reflected in the non-royal funerary spells found in the Coffin Text and the Book of the Dead (The Book of Coming Forth by Day), even though these do not contain elaborate descriptions of hell either. That is not very surprising, considering that these spells take for granted that their owners will not be judged favorably in the weighing of their hearts in the afterlife. Spells that mention the dangers of the world of the damned, which the blessed dead pass on their nightly journey are plentiful, but these spells are aimed principally at steering clear of such dangers, and the subject of the fate of the damned is therefore usually avoided as well.

On the other hand, the role of the dead king is different. During his life he was required, as the incarnation and representative of the sun god, to maintain the cosmic and social order (ma'at) established by the god of creation. He had to repel the forces of chaos which constantly threatened the order of the world. After his death, the king united with the sun disk and his divine body merged with his creator. In this new role he continued to perform the task of subduing the powers of chaos. This active role of the king and sun god necessitated a detailed description of the punishment of the damned, who represent the forces of evil. Their fate is therefore described in terms similar to those used for earthly adversaries of the king and of Egypt. They became enemies who are "reckoned with," "overthrown," "repelled," and "felled". The precise nature of the deeds that bought them to this fate are never stipulated, nor is there a direct relationship between their punishment and the crimes that they committed during their lives. There are no separate areas in hell for different categories of evildoers, nor is there any sort of Purgatory, where sinners can repent and be admitted to the company of the followers of Re at a later stage.

The crimes of those who are condemned to hell consist of nothing more and nothing less than having acted against the divine world order established at the beginning of creation. Hence, they have excluded themselves from ma'at, while at the same time revealing themselves as agents of chaos. After death, they became forever reduced to a state of nonbeing., which was the chaotic state of the cosmos before creation. For them, there is no renewal and no regeneration of life, but only a second, definitive death. Rather than being the followers of Re, they are the "gang of Seth." Seth is the god who brought death into the world by murdering Osiris. They might also be referred to as the "children of Nut." Nut was the mother of Seth, and therefore of the first generation of mankind who rebelled against Re.

In every respect, the fate of the damned is the opposite of that of the blessed. When the righteous died and were mummified and buried with the proper rites, they could expect to start a new life in the company of Re and Osiris. The ritual known as the Opening of the Mouth ensured that they would regain control over their senses. Their bodies rest in their tombs until sunrise, when Re is reborn form the underworld in the east. Then, their ba-souls leave the tomb unhindered and join the sun god. They spend a wonderful time in the Field of Rushes (paradise), where they have abundant cool air, food, drink and even sexual pleasures. At night, when Re once more enters the underworld in the west and unites with Osiris, they return to their mummified bodies.

However, when the damned died, their flesh was torn away by demons and their mummy wrappings were removed so that their bodies were left to decompose. In the underworld that the blessed successfully navigate, their order of things is reversed, even to the extent that the damned have to walk upside down, eat their own excrement and drink their own urine. Their hands are tied behind their backs, often around stakes. Their heads and limbs are severed from their bodies and their flesh is cut off their bones. Their hearts are removed and their ba-souls are separated from their bodies, forever unable to return to them. They even loose their shadows, which were considered an important part of the ancient Egyptian being. They have no air and suffer from hunger and thirst, as they receive no funerary offerings. Worst of all, they are denied the reviving light of the sun god, who ignores them, even as they cry out load and wail when he passes them in the underworld at night.

Hence, they are excluded from the eternal cosmic cycle of renewal and are instead assigned to the "outer darkness, the primeval chaotic world before creation, which is situated in the deepest recesses of the underworld, outside the created world. They are continuously punished by demons, who are the representatives of chaos. Indeed, the demons are often recruited from the ranks of the damned themselves, so that they torture and kill one another. They are subjected to knives and swords and to the fire of hell, often kindled by fire spitting snakes.

These horrible punishments were carried out in the "slaughtering place" or "place of destruction", and presided over by the fierce goddess Sekhmet, whose butchers hack their victims to pieces and burn them with inextinguishable fire, sometimes in deep pits or in cauldrons in which they are scorched, cooked and reduced to ashes. Demons feed on their entrails and drink their blood.

Another location was the Lake of Fire, which was first mentioned in the Book of Two Ways in the Coffin Text (Spell 1054/1166) and illustrated in the Book of the Dead (Chapter 126). Like the "outer darkness," it is a place of regeneration for the sun god and his blessed followers, to whom it provides nourishment and cool water, but a place of destruction for the damned. Birds even fly away from it when they experience the burning, bloody water and small the stench of putrefaction which rises from it. In chapter 126 of the Book of the Dead, its shores are guarded by four baboons who sit at the bow of the barque of Re and who are usually connected to the sunrise. There, they act as judges of the divine tribunal in order to decide who might be granted access through "the secret portals of the West" and who will be delivered to the hellhound, who, according to another spell, is in charge of this place. That demon is the "Swallower of Millions," responsible for devouring corpses, or their shadows, snatching hearts and inflicting injury without being seen.

Judgment of the Dead from the Book of the Dead

By the end of the 18th Dynasty, a similar demon appears in chapter 125 of the Book of the Dead that depicts the judgment of the deceased before the divine tribunal. This is the better known judgment of the dead in which the heart of the deceased is weighed against the feather of Ma'at on a scale. In many cases, the Lake of Fire in Chapter 126 is also shown in this chapter. A late, Demontic text tells us that if the deceased's "evil deeds outnumber his good deeds he is delivered to the Swallower....; his soul as well as his body are destroyed and never will he breath again." In the vignette this monster is called the "Swallower of the Damned". The demon (Ammit) is represented with the head of a crocodile, the forelegs and body of a lion and the hindquarters of a hippopotamus. The demon might also sometimes be referred to as the "beast of destiny". She usually sits near the balance, ready to devour her victim. However, since the owner of the Book of the Dead in question is naturally supposed to survive the judgment, the Swallower is almost never shown grabbing her victim.

*******************************************

Ani Papyrus * Afterlife from the book of coming forth by day.

There are, however, a few late instances dating to Roman times that do show the demon's wrath. In one instance, the monster is sitting beside a fiery cauldron into which the emaciated bodies of the damned, stripped of their mummy wrappings, are thrown. At this late period, Egyptian concepts began to be influenced by images from elsewhere in the Hellenistic world, as is illustrated by a representation of the Swallower that is very reminiscent of the Greek Sphinx, who was also a demon of fate and death.

In turn, later Egyptian representations of the Christian hell, from Coptic and other early Christian texts, may well have influenced medieval European descriptions and depictions of the Inferno.

********************************

References:

Title Author Date Publisher Reference Number

Ancient Gods Speak, The: A Guide to Egyptian Religion Redford, Donald B. 2002 Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-515401-0

Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt, The Wilkinson, Richard H. 2003 Thames & Hudson, LTD ISBN 0-500-05120-8

Dictionary of Ancient Egypt, The Shaw, Ian; Nicholson, Paul 1995 Harry N. Abrams, Inc., Publishers ISBN 0-8109-3225-3

Life of the Ancient Egyptians Strouhal, Eugen 1992 University of Oklahoma Press ISBN 0-8061-2475-x

Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, The Redford, Donald B. (Editor) 2001 American University in Cairo Press, The ISBN 977 424 581 4

Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, The Shaw, Ian 2000 Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-815034-2

Egyptian Heaven and Hell*

HAVING briefly referred to the origin and development of the magical, religious, and purely funeral texts which, sometimes with and sometimes without illustrations, formed the "Guides" to the Ancient Egyptian Underworld, the form of the conceptions concerning the place of departed spirits as it appears in the Recensions of the XVIIIth and XIXth Dynasties must now be considered. To reconstruct the form which they took in the Predynastic Period is impossible, for no materials exist, and the documents of the Early Empire are concerned chiefly with providing the deceased with an abundance of meat, drink, and other material comforts, and numbers of wives and concubines, and a place in Sekhet-Aaru, a division of Sekhet-hetepet, to which the name "Elysian Fields" has not inaptly been given. In later times Sekhet-Aaru, or Sekhet-Aanru, comprised all Sekhet-hetepet. Of Sekhet-hetepet as a whole the earliest known pictures are those which are painted on the coffins of

p. 28

Al-Barsha, and of no portion of this region have we any detailed illustrations of the occupations of its inhabitants older than the XVIIIth Dynasty. To the consideration of Sekhet-Aaru, which was the true heaven of every faithful worshipper of Osiris, from the time when he became the judge and benevolent god and friend of the dead down to the, Ptolemaïc Period, that is to say, for a period of four thousand years at least, the scribes and artists of the XVIIIth Dynasty devoted much attention, and the results of their views are set forth in the copies of PER-EM-HRU, or the Theban Book of the Dead, which have come down to us.

In one of the oldest copies of PER-EM-HRU, i.e., in the Papyrus of Nu, 1 is a vignette of the Seven Arits, or divisions of Sekhet-Aaru; the portion shown of each Arit is the door, or gate, which is guarded by a gatekeeper, by a watcher, who reports the arrival of every comer, and by a herald, who receives and announces his name. All these beings save two have the head of an animal, or bird, on a human body, a fact which indicates the great antiquity of the ideas that underlie this vignette. Their names are:--

Arit I. Gatekeeper. SEKHET-HRA-ASHT-ARU.

Watcher. SEMETU.

Herald. HU-KHERU.

p. 29

Click to view

The Seven Arits, each with its Gatekeeper, its Watcher, and its Herald.

p. 31

Arit II. Gatekeeper. TUN-HAT.

Watcher. SEQET-HRA.

Herald. SABES.

Arit III. Gatekeeper. AM-HUAT-ENT-PEHUI-FI.

Watcher. RES-HRA.

Herald. UAAU.

Arit IV. Gatekeeper. KHESEF-HRA-ASHT-KHERU.

Watcher. RES-AB.

Herald. NETEKA-HRA-KHESEF-ATU.

Arit V. Gatekeeper. ANKH-EM-FENTU.

Watcher. ASHEBU.

Herald. TEB-HER-KEHAAT.

Arit VI. Gatekeeper. AKEN-TAU-K-HA-KHERU.

Watcher. AN-HRA.

Herald. METES-HRA-ARI-SHE.

Arit VII. Gatekeeper. METES-SEN.

Watcher. AAA-KHERU.

Herald. KHESEF-HRA-KHEMIU.

From another place in the same papyrus, 1 and from other papyri, we learn that the "Secret Gates of the House of Osiris in Sekhet-Aaru" were twenty-one in number; the Chapter (CXLVI.) gives the name of each Gate, and also that of each Gatekeeper up to No. X., thus:--

I. Gate. NEBT-SETAU-QAT-SEBT-HERT-NEBT-KHEBKHEBT-SERT-METU-KHESEFET-NESHENIU-NEHEMET-UAI-EN-I-UAU.

p. 32

Gatekeeper. NERI.

II. Gate. NEBT-PET-HENT-TAUI-NESBIT-NEBT-TEMEMU-TENT-BU-NEBU.

Gatekeeper. MES-PEH. (or, MES-PTAH).

Click to view

Gate I.

Click to view

Gate II.

III. Gate. NEBT-KHAUT-AAT-AABET-SENETCHEMET-NETER-NEB-AM-S-HRU-KHENT-ER-ABTU.

Gatekeeper. ERTAT-SEBANQA.

IV. Gate. SEKHEMET-TESU-HENT-TAUI-HETCHET-KHEFTI-NU-URT-AB-ARIT-SARU-SHUT-EM-AU.

Gatekeeper. NEKAU.

p. 33

Click to view

Gate III.

Click to view

Gate IV.

V. Gate. NEBT-REKHU-RESHT-TEBHET-TATU-AN-AQ-ERES-UN-TEP-F.

Gatekeeper. HENTI-REQU.

Click to view

Gate V.

Click to view

Gate VI.

p. 34

VI. Gate. NEBT-SENKET-AAT-HEMHEMET-AN-REKH-TU-QA-S-ER-USEKH-S-AN-QEMTU-QET-S-EM-SHAA-AU-HEFU-HER-S-AN-REKH-TENNU-MES-EN-THU-KHER-HAT-URTU-AB.

Gatekeeper. SMAMTI.

Click to view

Gate VII.

Click to view

Gate VIII.

VII. Gate. AKKIT-HEBSET-BAK-AAKEBIT-MERT-SEHAP-KHAT.

Gatekeeper. AKENTI.

VIII. Gate. REKHET-BESU-AKHMET-TCHAFU-SEPT-PAU-KHAT-TET-SMAM-AN-NETCHNETCH-ATET-SESH-HER-S-EN-SENT-NAH-S.

Gatekeeper. KHU-TCHET-F.

p. 35

IX. Gate. AMT-HAT-NEBT-USER-HERT-AB-MESTET-NEB-S-KHEMT-SHAA-. . . .-EM-SHEN-S-SATU-EM-UATCHET-QEMA-THESET-BES-HEBSET-BAK-FEQAT-NEB-S-RA-NEB.

Gatekeeper. TCHESEF.

Click to view

Gate IX.

Click to view

Gate X.

X. Gate. QAT-KHERU-NEHESET-TENATU-SEBHET-ER-QA-EN-KHERU-S-NERT-NEBT-SHEFSHEFT-AN-TER-S-NETET-EM-KHENNU-S.

Gatekeeper. SEKHEN-UR.

XI. Gate. NEMT-TESU-UBTET-SEBAU-HENT-ENT-SEBKHET-NEBT-ARU-NES-AHEHI-HRU-EN-ANKHEKH. 1

p. 36

XII. Gate. NAST-TAUI-SI-SEKSEKET-NEMMATU-EM-NEHEPU-QAHIT-NEBT-KHU-SETEMTH-KHERU-NEB-S.

XIII. Gate. STA-EN-ASAR-AAUI-F-HER-S-SEHETCHET-HAP-EM-AMENT-F.

XIV. Gate. NEBT-TENTEN-KHEBT-HER-TESHERU-ARU-NES-HAKER-HRU-EN-SETEMET-AU.

XV. Gate. BATI-TESHERU-QEMHUT-AARERT-PERT-EM-KERH-SENTCHERT-SEBA-HER-QABI-F-ERTAT-AAUI-S-EN-URTU-AB-EM-AT-F-ART-ITET-SHEM-S.

XVI. Gate. NERUTET-NEBT-AATET-KHAA-KHAU-EM-BA-EN-RETH-KHEBSU-MIT-EN-RETH-SERT-PER-QEMAMET-SHAT.

XVII. Gate. KHEBT-HER-SENF-AHBIT-NEBT-UAUIUAIT.

XVIII. Gate. MER-SETAU-AB-ABTU-MERER-S-SHAT-TEPU-AMKHIT-NEBT-AHA-UHSET-SEBAU-EM-MASHERU.

XIX. Gate. SERT-NEHEPU-EM-AHA-S-URSH-SHEMMET-NEBT-USERU-ANU-EN-TEHUTI-TCHESEF.

XX. Gate. AMT-KHEN-TEPEH-NEB-S-HEBS-REN-S-AMENT-QEMAMU-S-THETET-HATI-EN-AM-S.

XXI. Gate. TEM-SIA-ER-METUU-ARI-HEMEN-HAI-NEBAU-S.

From the above lists, and from copies of them which are found in the Papyrus of Ani, and other

p. 37

finely illustrated Books of the Dead, it is quite clear that, according to one view, Sekhet-Aaru, the land of the blessed, was divided into seven sections, each of which was entered through a Gate having three attendants, and that, according to other traditions, it had sections varying in number from ten to twenty-one, for each of the Gates mentioned above must have been intended to protect a division. It will be noted that the names of the Ten Gates are in reality long sentences, which make sense and can be translated, but there is little doubt that under the XVIIIth Dynasty these sentences were used as purely magical formulae, or words of power, which, provided the deceased knew how to pronounce them, there was no great need to understand. In other words, it was not any goodness or virtue of his own which would enable him to pass through the Gates of Sekhet-Aaru, and disarm the opposition of their warders, but the knowledge of certain formulæ, or words of power, and magical names. We are thus taken back to a very remote period by these ideas, and to a time when the conceptions as to the abode of the blessed were of a purely magical character; the addition of pictures to the formulae, or names, belongs to a later period, when it was thought right to strengthen them by illustrations. The deceased, who not only possessed the secret name of a god or demon, but also a picture of him whereby he could easily recognize him when he met him, was doubly armed against danger.

p. 38

In addition to the Seven Arits, and the Ten, Fourteen, or Twenty-one Gates (according to the manuscript authority followed), the Sekhet-Hetepet possessed Fourteen or Fifteen Aats, or Regions, each of which was presided over by a god. Their names, as given in the Papyrus of Nu, 1 are as follows:--

Aat I. AMENTET wherein a man lived on cakes and ale; its god was AMSU-QET, or MENU-QET.

Aat II. SEKHET-AARU. Its walls are of iron. The wheat here is five cubits high, the barley

Click to view

Aat I.

Click to view

Aat II.

is seven cubits high, and the Spirits who reap them are nine cubits high. The god of this Aat is RA-HERUKHUTI.

Aat III. AATENKHU. Its god was OSIRIS or RA.

Aat IV. TUI-QAUI-AAUI. Its god was SATI-TEMUI.

Aat V. AATENKHU. The Spirits here live upon the inert and feeble. Its god was probably OSIRIS.

p. 39

Click to view

Aat III.

Click to view

Aat IV.

Click to view

Aat V.

Aat VI. AMMEHET, which is presided over either by SEKHER-AT or SEKHER-REMUS. This was sacred to the gods, the Spirits could not find it out, and it was accursed for the dead.

Aat VII. ASES, a region of burning, fiery flame, wherein the serpent REREK lives.

Aat VIII. HA-HETEP, a region containing roaring torrents of water, and ruled over by a god called QA-HA-HETEP. A variant gives the name of this Aat as HA-SERT, and that of its god as FA-PET.

Click to view

Aat VI.

Click to view

Aat VII.

Click to view

Aat VIII.

p. 40

Click to view

Aat IX.

Click to view

Aat X.

Aat IX. AKESI, a region which is unknown even to the gods; its god was MAA-THETEF, and its only inhabitant is the "god who dwelleth in his egg."

Aat X. NUT-ENT-QAHU, i.e., the city of Qahu. It was also known by the name APT-ENT-QAHU. The gods of this region appear to have been NAU, KAPET, and NEHEB-KAU.

Aat XI. ATU, the god of which was SEPT (Sothis).

Aat XII. UNT, the god of which was HETEMET-BAIU; also called ASTCHETET-EM-AMENT.

Click to view

Aat XI.

Click to view

Aat XII.

p. 41

Aat XIII. UART-ENT-MU: its deity was the hippopotamus-god called HEBT-RE-F.

Aat XIV. The mountainous region of KHER-AHA, the god of which was HAP, the Nile.

A brief examination of this list of Aats, or Regions, suggests that the divisions of Sekhet-hetepet given in it are arranged in order from south to north, for it is well known that Amentet, the first Aat, was entered from the neighbourbood of Thebes, and that the last-mentioned Aat, i.e., Kher-aha, represents a region quite

Click to view

Aat XIII.

Click to view

Aat XIV.

close to Heliopolis; if this be so, Sekhet-Aaru was probably situated at no great distance from Abydos, near which was the famous "Gap" in the mountains, whereby the spirits of the dead entered the abode set apart for them. We see from this list also that the heaven provided for the blessed was one such as an agricultural population would expect to have, and a nation of farmers would revel in the idea of living among fields of wheat and barley, the former being

p. 42

between seven and eight feet, and the latter between nine and ten feet high. The spirits who reaped this grain are said to have been nine cubits, i.e., over thirteen feet, in height, a statement which seems to indicate that a belief in the existence of men of exceptional height in very ancient days was extant in Egypt traditionally.

Other facts to be gleaned from the list of Aats concerning Sekhet-Aaru are that:--1. One section at least was filled with fire. 2. Another was filled with rushing, roaring waters, which swept everything away before them. 3. In another the serpent Rerek lived. 4. In another the Spirits lived upon the inert and the feeble. 5. In another lived the "Destroyer of Souls." 6. The great antiquity of the ideas about the Aats is proved by the appearance of the names of Hap, the Nile-god, Sept, or Sothis, and the Hippopotamus-goddess, Hebt-re-f, in connection with them.

The qualification for entering the Aats was not so much the living of a good life upon earth as a knowledge of the magical figures which represented them, and their names; these are given twice in the Papyrus of Nu, and as they are of great importance for the study of magical pictures they have been reproduced above.

Of the general form and the divisions of Sekhet-Aaru, or the "Field of Reeds," and Sekhet-hetepet, or the "Field of Peace," thanks to the funeral papyri of the XVIIIth Dynasty, much is known, and they

p. 43

may now be briefly described. From the Papyrus of Nebseni 1 we learn that Sekhet-hetep was rectangular in shape, and that it was intersected by canals, supplied from the stream by which the whole region was enclosed. In one division were three pools of water,

Click to view

Sekhet-Hetepet (Papyrus of Nebseni, British Museum, No. 9900, sheet 17).

in another four pools, and in a third two pools; a place specially set apart was known as the "birthplace of the god of the region," and the "great company of the

p. 44

gods in Sekhet-hetep" occupied another section of it. At the end of a short canal was moored a boat, provided with eight oars or paddles, and each end of it terminated in a serpent's head; in it was a flight of steps. The deceased, as we see, also possessed a boat wherein he sailed about at will, but its form is different from that of the boat moored at the end of the canal. The operations of ploughing, and of seed-time and harvest, are all represented. As to the deceased himself, we see him in the act of offering incense to the "great company of the gods," and he addresses a bearded figure, which is intended probably to represent his father, or some near relation; we see him paddling in a boat, and also sitting on a chair of state smelling a flower, with a table of offerings before him. None of the inscriptions mentions Sekhet-Aaru, but it is distinctly said that the reaping of the grain by the deceased is taking place in Sekhet-hetep, or Sekhet-hetepet.

In chronological order the next picture of Sekhet-hetepet to be considered is that from the Papyrus of Ani, and it will be seen at a glance that in details it differs from that already described. Ani adores the gods in the first division, but he burns no incense; the boat in which he paddles is loaded with offerings, and he is seen dedicating an offering to the bearded figure. The legend reads, "Living in peace in Sekhet--winds for the nostrils." The second division contains scenes

p. 45

Click to view

Sekhet-Hetepet (Papyrus of Ani, British Museum, No. 10,740, sheet 32).

p. 47

of' reaping and treading out of corn, but only three pools of water instead of four. In the third division we see An! ploughing the land by the side of a stream of untold length and breadth, which is said to contain neither fish nor worms. It is important to note that this division is described as SEKHET-AANRU. The eyot which represents the birthplace of the god of the city has no title, and the larger island, which is separated from it by a very narrow strip of ground, contains a flight of steps, but no gods. In the left-hand corner is a place which is described as "the seat of the Spirits, who are seven cubits in height"; the "grain is three cubits high, and it is the perfect Spirits who reap it." In the other portion of this section are two boats instead of one as in the Papyrus of Nebseni.

In connection with the two pictures of Sekhet-hetepet described above, it is important to consider the text which accompanies the older of them, i.e., that of the Papyrus of Nebseni. The deceased is made to say that he sails over the Lake of Hetep (i.e., Peace) in a boat which he brought from the house of Shu, and that he has come to the city of Hetep under the favour of the god of the region, who is also called Hetep. He says, "My mouth is strong, I am equipped [with words of power to use as weapons] against the Spirits let them not have dominion over me. Let me be rewarded with thy fields, O thou god Hetep. That

p. 48

which is thy wish do, O lord of the winds. May I become a spirit therein, may I eat therein, may I drink therein, may I plough therein, may I reap therein, may I fight therein, may I make love therein, may my words be powerful therein, may I never be in a state of servitude therein, and may I be in authority therein . . . . . . [Let me] live with the god Hetep, clothed, and not despoiled by the 'lords of the north,' 1 and may the lords of divine things bring food unto me. May he make me to go forward and may I come forth; may he bring my power to me there, may I receive it, and may my equipment be from the god Hetep. May I gain dominion over the great and mighty word which is in my body in this my place, and by it I shall have memory and not forget." The pools and places in Sekhet-hetepet which the deceased mentions as having a desire to visit are UNEN-EM-HETEP, the first large division of the region; NEBT-TAUI, a pool in the second division; NUT-URT, a pool in the first division; UAKH, a pool in the second division, where the kau, or "doubles," dwell; TCHEFET, a portion of the third division, wherein the deceased arrays himself in the apparel of Ra; UNEN-EM-HETEP, the birthplace of the Great God; QENQENTET, a pool in the first division, where he sees his father, and

p. 49

looks upon his mother, and has intercourse with his wife, and where he catches worms and serpents and frees himself from them; the Lake of TCHESERT, wherein he plunges, and so cleanses himself from all impurities; HAST, where the god ARI-EN-AB-F binds on his head for him; USERT, a pool in the first division, and SMAM, a pool in the third division of Sekhet-hetepet. Having visited all these places, and recited all the words of power with which he was provided, and ascribed praises to the gods, the deceased brings his boat to anchor, and, presumably, takes up his abode in the Field of Peace for ever.

From the extract from the Chapter of Sekhet-Aaru and Sekhet-hetepet given above, it is quite clear that the followers of Osiris hoped and expected to do in the next world exactly what they had done in this, and that they believed they would obtain and continue to live their life in the world to come by means of a word of power; and that they prayed to the god Hetep for dominion over it, so that they might keep it firmly in their memories, and not forget it. This is another proof that in the earliest times men relied in their hope of a future life more on the learning and remembering of a potent name or formula than on the merits of their moral and religious excellences. From first to last throughout the chapter there is no mention of the god Osiris, unless he be the "Great God" whose birthplace is said to be in the region Unen-em-hetep, and nowhere in it is there any suggestion that the

p. 50

permission or favour of Osiris is necessary for those who would enter either Sekhet-Aaru or Sekhet-hetep. This seems to indicate that the conceptions about the Other World, at least so far as the "realms of the blest" were concerned, were evolved in the minds of Egyptian theologians before Osiris attained to the high position which he occupied in the Dynastic Period. On the other hand, the evidence on this point which is to be deduced from the Papyrus of Ani must be taken into account.

At the beginning of this Papyrus we have first of all Hymns to Ra and Osiris, and the famous Judgment Scene which is familiar to all. We see the heart of Ani being weighed in the Balance against the symbol of righteousness in the presence of the Great Company of the Gods, and the weighing takes place at one end of the house of Osiris, whilst Osiris sits in his shrine at the other. The "guardian of the Balance" is Anubis, and the registrar is Thoth, the scribe of the gods, who is seen noting the result of the weighing. In the picture the beam of the Balance is quite level, which shows that the heart of Ani exactly counterbalances the symbol of righteousness. This result Thoth announces to the gods in the following words, "In very truth the heart of Osiris hath been weighed, and his soul hath stood as a witness for him; its case is right (i.e., it hath been found true by trial) in the Great Balance. No wickedness hath been found in him, he hath not purloined the offerings in the

p. 51

temples, 1 and he hath done no evil by deed or word whilst he was upon earth." The gods in their reply accept Thoth's report, and declare that, so far as they are concerned, Ani has committed neither sin nor evil. Further, they go on to say that he shall not be delivered over to the monster Amemet, and they order that he shall have offerings, that he shall have the power to go into the presence of Osiris, and that he shall have a homestead, or allotment, in Sekhet-hetepet for ever. We next see Ani being led into the presence of Osiris by Horus, the son of Isis, who reports that the heart of Ani hath sinned against no god or goddess; as it hath also been found just and righteous according to the written laws of the gods, he asks that Ani may have cakes and ale given to him, and the power to appear before Osiris, and that he may take his place among the "Followers of Horus," and be like them for ever.

Now from this evidence it is clear that Ani was considered to have merited his reward in Sekhet-hetepet by the righteousness and integrity of his life upon earth as regards his fellow-man, and by the reverence and worship which he paid to every god and every goddess; in other words, it is made to appear that he had earned his reward, or had justified himself by his works. Because his heart had emerged

p. 52

triumphantly from its trial the gods decreed for him the right to appear in the presence of the god Osiris, and ordered him to be provided with a homestead in Sekhet-hetep. There is no mention of any repentance on Ani's part for wrong done; indeed, he says definitely, "There is no sin in my body. I have not uttered wittingly that which is untrue, and I have committed no act having a double motive [in my mind]." As he was troubled by no remembrance of sin, his conscience was clear, and he expected to receive his reward, not as an act of mercy on the part of the gods, but as an act of justice. Thus it would seem that repentance played no part in the religion of the primitive inhabitants of Egypt, and that a man atoned for his misdeeds by the giving of offerings, by sacrifice, and by worship. On the other hand, Nebseni is made to say to the god of Sekhet-hetep, "Let me be rewarded with thy fields, O Hetep; but do thou according to thy will, O lord of the winds." This petition reveals a frame of mind which recognizes submissively the omnipotence of the god's will, and the words "do thou according to thy will" are no doubt the equivalent of those which men of all nations and in every age have prayed--"Thy will be done."

The descriptions of the pictures of Sekhet-hetep given above make it evident that the views expressed in the Papyrus of Nebseni differ in some important details from those which we find in the Papyrus of Ani, but whether this difference is due to some general

p. 53

Click to view

Sekhet-hetepet, showing the Sekhet-Aaru, with the magical boat and flight of steps, the birthplace of the gods, &c. (From the inner coffin of Kua-tep, British Museum, No. 30,840.)

p. 55

Click to view

Sekhet-hetepet, showing the Sekhet-Aaru with the magical boat, the nine lakes, the birthplace of the gods, &c. (From the outer coffin of Sen, British Museum, No. 30,841.)

p. 57

development in religious thought, which took place in the interval between the periods when the papyri were written, cannot be said. There is abundant evidence in the Papyrus of Ani that Ani himself was a very religious man, and we are not assuming too much when we say that he was the type of a devout worshipper of Osiris, whose beliefs, though in some respects of a highly spiritual character, were influenced by the magic and gross material views which seem to have been inseparable from the religion of every Egyptian. Though intensely logical in some of their views about the Other World, the Egyptians were very illogical in others, and they appear to have seen neither difficulty nor absurdity in holding at the same time beliefs which were inconsistent and contradictory. It must, however, in fairness be said that this characteristic was due partly to their innate conservatism in religious matters, and their respect for the written word, and partly to their fear that they might prejudice their interests in the future life if they rejected any scripture or picture which antiquity, or religious custom, or tradition had sanctioned.

Certain examples, however, prove that the Egyptians of one period were not afraid to modify or develop ideas which had come down to them from another, as may be seen from the accompanying illustration. The picture which is reproduced on p. 53 is intended to represent Sekhet-hetepet, and is taken from the inner coffin of Kua-Tep, which was found at Al-Barsha, and is now

p. 58

in the British Museum (No. 30,840); it dates front the period of the XIth Dynasty. From this we see that the country of the blessed was rectangular in shape, and surrounded by water, and intersected by streams, and that, in addition to large tracts of land, there were numbers of eyots belonging to it. In many pictures these eyots are confounded with lakes, but it is pretty clear that the "Islands of the Blessed" were either fertile eyots, or oases which appeared to be green islands in a sea of sand. Near the first section were three, near the second four, near the third four, three, being oval, and one triangular; the fourth section was divided into three parts by means of a canal with two arms, and contained the birthplace of the god, and near it were seven eyots; the fifth is the smallest division of all, and has only one eyot near it. Each eyot has a name which accorded with its chief characteristic; the dimensions of three of the streams or divisions are given, the region where ploughing takes place is indicated, and the positions of the staircase and the mystic boat are clearly shown. The name of the god Hetep occurs twice, and that of Osiris once.

If now we compare this picture with that front the Papyrus of Nebseni we shall find that the actual operations of ploughing, reaping, and treading out of the corn are depicted on the Papyrus, and that several figures of gods and the deceased have been added. The text speaks of offerings made by the deceased, and of his sailing in a boat, &c., therefore the artist

p. 59

Click to view

Sekhet-hetepet. (From the Papyrus of Anhai--XXIInd Dynasty.)

p. 61

Click to view

Sekhet-hetepet. (From the Turin Papyrus-Ptolemaïc Period.)

p. 63

added scenes in which he is depicted doing these things; and the lower part of the picture in the Papyrus has been modified considerably. In the second division it may be noted that Nebseni is seen laying both hands on the back of the Bennu bird; there is no authority for this in the older copy of the picture. In the illustration on p. 55, which is reproduced from the coffin of Sen, in the British Museum (No. 30,841), a still simpler form of Sekhet-hetepet is seen; here we have only nine eyots, which are grouped together, and no inscription of any kind.

Still further modifications were introduced into the pictures of Sekhet-hetepet drawn in later times, and, in order that the reader may be enabled to trace some of the most striking of these, copies of Sekhet-hetepet from the Papyrus of Anhai (about B.C. 1040), and from that of Auf-ankh (Ptolemaïc Period), are reproduced on pp. 59 and 61.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Footnotes

28:1 British Museum, No. 10,477, sheet 26 (Chapter cxliv.).

31:1 Sheet 25.

35:1 The names of the gatekeepers of Gates XL-XXI. are not given in the papyri.

38:1 Sheets 28, 29, and 30.

43:1 British Museum, No. 9,900, sheet 17.

48:1 Probably the marauding seamen who traded on the coasts of the Mediterranean, and who sometimes landed and pillaged the region near which the primitive Elysian Fields were supposed to have been situated.

51:1 Ani was the receiver of the ecclesiastical revenues of the gods of Thebes and Abydos, and the meaning here is that he did not divert, to his own use any portion of the goods he received.